On April 29, 2005, two people—45-year-old Matthew Nannen and 58-year-old Bailee Crane—died after falling from a viewing area at Bryce Canyon National Park in southern Utah, authorities said.

On April 29, 2005, two people—45-year-old Matthew Nannen and 58-year-old Bailee Crane—died after falling from a viewing area at Bryce Canyon National Park in southern Utah, authorities said.

A seemingly ordinary hike in Death Valley National Park turned tragic on April 5th. A 66-year-old Gig Harbor, Washington man lost his life about a mile up the Mosaic Canyon Trail, apparently struck down by a sudden medical emergency.

There was a string of accidents in Grand Canyon National Park in 2019, involving multiple people falling to their deaths.

These reports – and others like them – led us to wonder:

How and how often do people die in America’s National Parks?

Which National Parks frequently have the most deaths?

We analyzed data from the National Parks Service (obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request) and found that thousands of people have died at U.S. National Parks since 2007.

In conjunction with data visualization agency 1Point21 Interactive, we analyzed the data and found the answer.

How often do people die in National Parks?

From 2007 to 2024, there were a total of 4,213 deaths at a U.S. National Parks site. While nearly 4,500 deaths is a very high number, it is spread across 17 years and hundreds of sites in the U.S. National Park system.

Additionally, there were over 5 billion recreation visits to National Parks during that time frame. That equates to just under 8 deaths per 10 million visits to park sites during that time frame.

We feel that it is important to say that, based on our data, visiting U.S National Parks is very safe overall. However, this analysis is driven by curiosity, so we carry on.

National Park Deaths: Who and How?

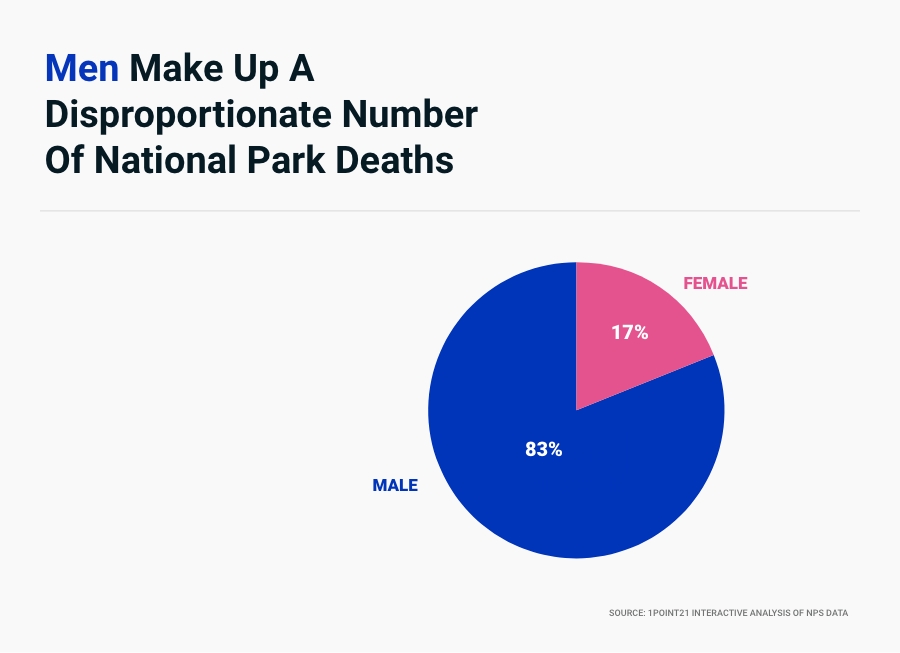

People of all ages and all walks of life visit our nation’s national parks. Yet men make up a disproportionate number of national park deaths, accounting for 83 percent of total fatalities.

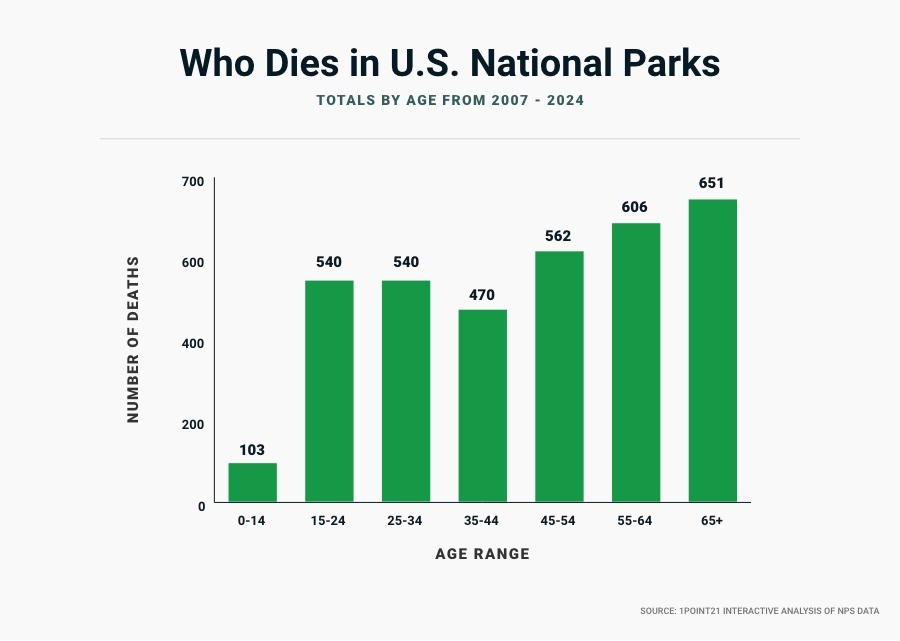

However, deaths are relatively evenly distributed among adult age ranges, with adults age 65+ leading the way at 19 percent. Thankful, children make up a very small portion of fatalities, with 103 deaths among children age 14 and under (3 percent).

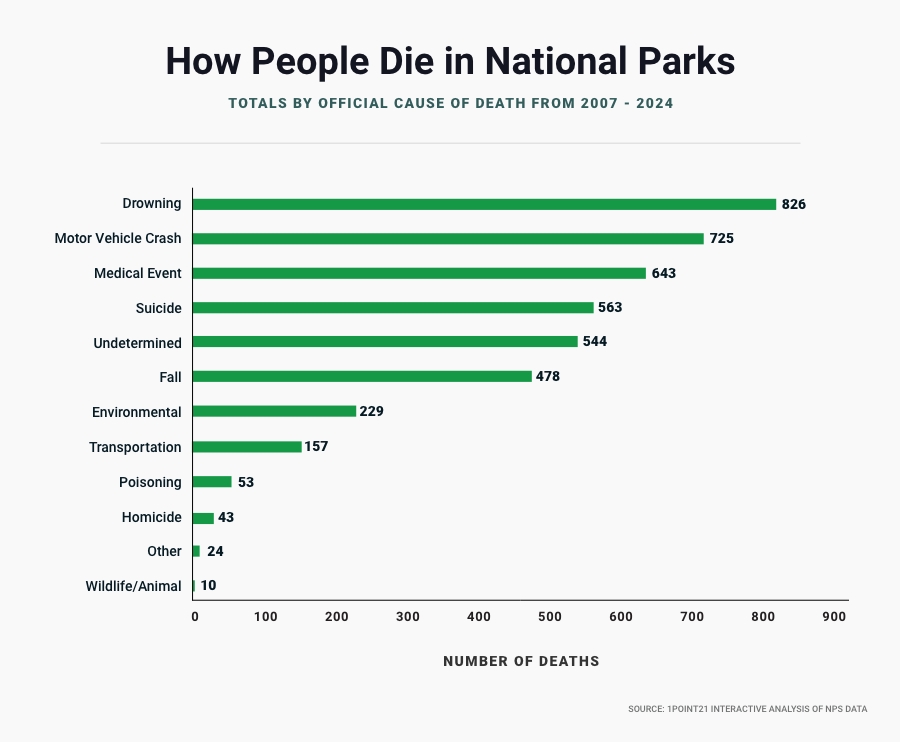

Drowning (826 deaths) is the Leading Cause of Death at national parks and national recreation areas.

Drowning is followed by motor vehicle crashes (725 deaths), medical events (643), suicide (563), undetermined (544), and falls and slips (478).

Interestingly, despite the abundance of wildlife at national parks, only ten people were killed by wild animals.

The number of car accidents may seem fairly high, but it makes sense, given the rural and scenic nature of most of these sites. Rural locations may empower drivers to exhibit more reckless habits with driving, such as not wearing seatbelts, speeding, distracted driving, and even driving under the influence.

Further, scenic national parks usually have twisting, winding roads through mountains that can be difficult to navigate even for the most competent drivers. The potential for a crash into a tree or another vehicle – or even to careen off the road – is very real.

Which National Park Are you Most Likely to Die at?

As you might expect, more people die at larger, more popular national parks and recreation areas. Only six parks saw more than 150 deaths during the study period:

- Lake Mead National Recreation Area – 317 deaths

- Grand Canyon National Park – 198 Deaths

- Yosemite National Park – 179 deaths

- Blue Ridge Parkway – 162 deaths

- Natchez Trace Parkway – 154 deaths

- Golden Gate National Recreation Area – 151 deaths

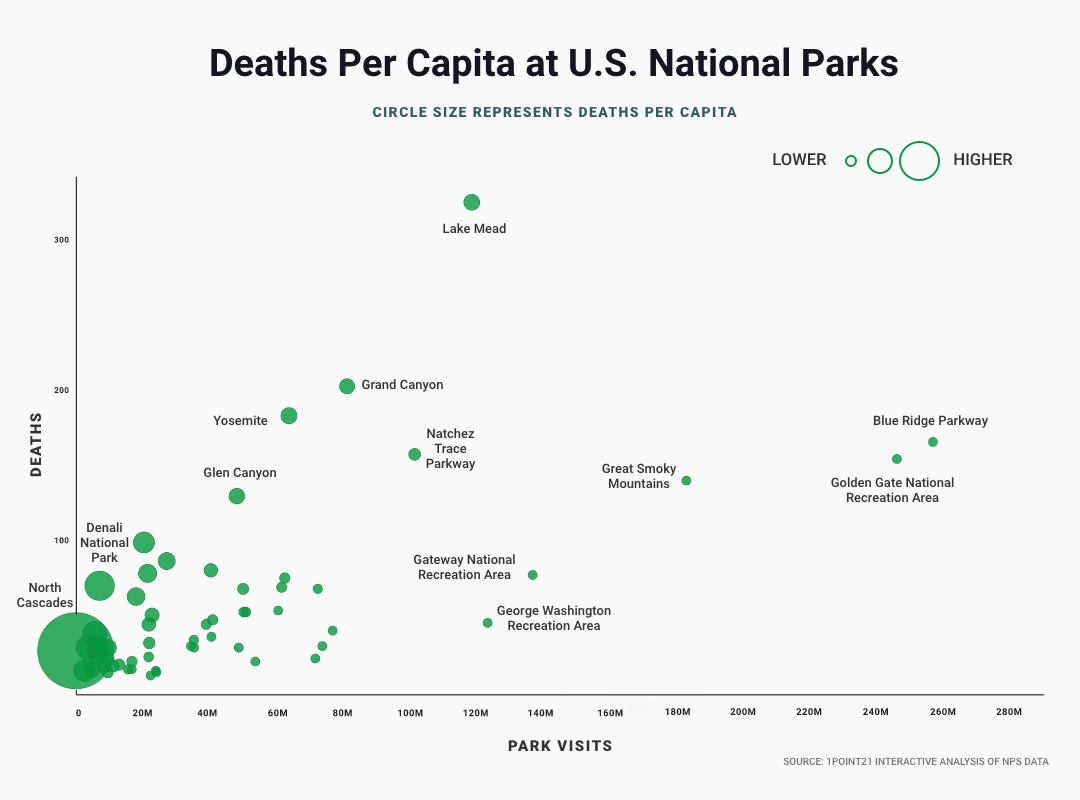

However, just because more people have died at those parks, doesn’t necessarily mean you are most likely to die there than you are at any other park. Consider that these are among the most visited parks in the nation. For instance, there were more than 120 million recreational visits to Lake Mead during the years we measured.

In order to effectively measure this, we collected the total estimated recreational visits for each park, then adjusted the total deaths per 10 million visits (minimum 10 total fatalities).

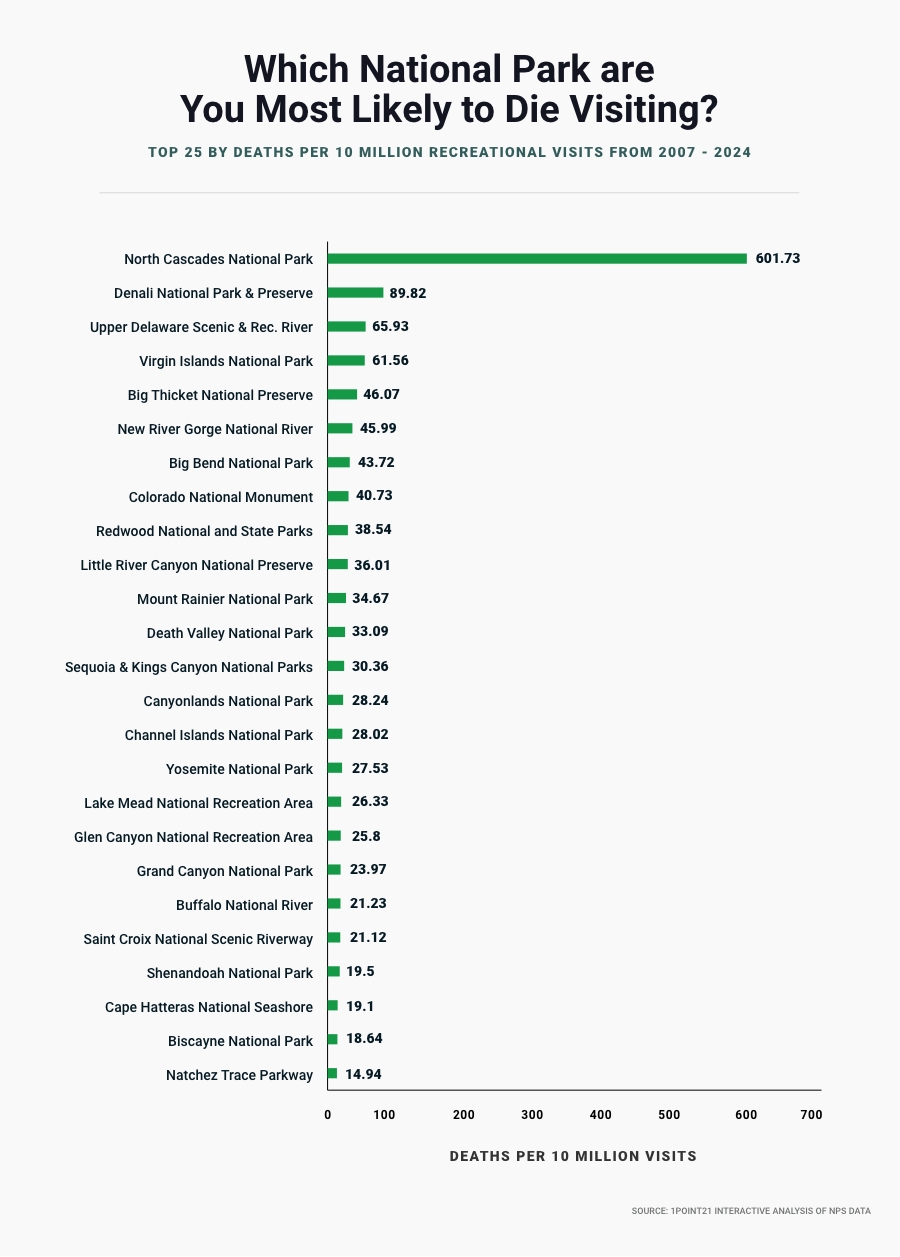

By this measure, you are – far and away – most likely to die at North Cascades National Park in Washington.

With only around 30,000 annual visitors, this 500,000-acre national park had the lowest total of any park with at least 10 fatalities. As a result, North Cascades National Park had a death rate of 601 per 10 million visits – 6.5 times higher than Denali National Park & Preserve (90) and nearly 22 times higher than the average (30).

| Rank | Park Name | Death Total | Park Visits (2007-2024) | Deaths per 10 Million Visits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | North Cascades National Park | 27 | 448,708 | 601.73 |

| 2 | Denali National Park & Preserve | 69 | 7,682,210 | 89.82 |

| 3 | Upper Delaware Scenic & Recreational River | 29 | 4,398,335 | 65.93 |

| 4 | Virgin Islands National Park | 38 | 6,172,810 | 61.56 |

| 5 | Big Thicket National Preserve | 14 | 3,039,164 | 46.07 |

| 6 | New River Gorge National River | 97 | 21,093,832 | 45.99 |

| 7 | Big Bend National Park | 30 | 6,861,174 | 43.72 |

| 8 | Colorado National Monument | 30 | 7,364,944 | 40.73 |

| 9 | Redwood National and State Parks | 28 | 7,264,789 | 38.54 |

| 10 | Little River Canyon National Preserve | 25 | 6,941,689 | 36.01 |

| 11 | Mount Rainier National Park | 77 | 22,212,167 | 34.67 |

| 12 | Death Valley National Park | 62 | 18,734,754 | 33.09 |

| 13 | Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks | 85 | 27,999,580 | 30.36 |

| 14 | Canyonlands National Park | 29 | 10,269,340 | 28.24 |

| 15 | Channel Islands National Park | 15 | 5,353,506 | 28.02 |

| 16 | Yosemite National Park | 179 | 65,021,252 | 27.53 |

| 17 | Lake Mead National Recreation Area | 317 | 120,374,610 | 26.33 |

| 18 | Glen Canyon National Recreation Area | 127 | 49,225,936 | 25.80 |

| 19 | Grand Canyon National Park | 198 | 82,611,849 | 23.97 |

| 20 | Buffalo National River | 50 | 23,550,712 | 21.23 |

| 21 | Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway | 21 | 9,942,441 | 21.12 |

| 22 | Shenandoah National Park | 44 | 22,561,741 | 19.50 |

| 23 | Cape Hatteras National Seashore | 79 | 41,351,599 | 19.10 |

| 24 | Biscayne National Park | 17 | 9,121,443 | 18.64 |

| 25 | Natchez Trace Parkway | 154 | 103,071,648 | 14.94 |

| 26 | Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area | 17 | 11,789,034 | 14.42 |

| 27 | Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area | 32 | 22,724,426 | 14.08 |

| 28 | Saguaro National Park | 18 | 13,614,001 | 13.22 |

| 29 | Grand Teton National Park | 67 | 51,128,854 | 13.10 |

| 30 | Padre Island National Seashore | 13 | 10,137,715 | 12.82 |

| 31 | Yellowstone National Park | 74 | 63,761,735 | 11.61 |

| 32 | Lake Meredith National Recreation Area | 20 | 17,462,161 | 11.45 |

| 33 | Glacier National Park | 47 | 41,923,244 | 11.21 |

| 34 | Point Reyes National Seashore | 44 | 39,963,967 | 11.01 |

| 35 | Rocky Mountain National Park | 68 | 62,790,939 | 10.83 |

| 36 | Ozark National Scenic Riverways | 23 | 22,523,291 | 10.21 |

| 37 | Olympic National Park | 52 | 51,316,597 | 10.13 |

| 38 | Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area | 52 | 51,981,826 | 10.00 |

| 39 | Rock Creek Park | 34 | 36,226,998 | 9.39 |

| 40 | Everglades National Park | 15 | 16,299,722 | 9.20 |

| 41 | Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area | 67 | 73,752,423 | 9.08 |

| 42 | Cuyahoga Valley National Park | 36 | 41,523,818 | 8.67 |

| 43 | Haleakala National Park | 15 | 17,384,026 | 8.63 |

| 44 | Zion National Park | 53 | 61,748,834 | 8.58 |

| 45 | Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore | 30 | 35,323,455 | 8.49 |

| 46 | Joshua Tree National Park | 29 | 36,304,700 | 7.99 |

| 47 | Great Smoky Mountains National Park | 137 | 185,345,712 | 7.39 |

| 48 | Blue Ridge Parkway | 162 | 260,028,371 | 6.23 |

| 49 | Golden Gate National Recreation Area | 151 | 249,101,891 | 6.06 |

| 50 | Acadia National Park | 29 | 49,820,730 | 5.82 |

| 51 | Hawaii Volcanoes National Park | 14 | 24,664,340 | 5.68 |

| 52 | Gateway National Recreation Area | 76 | 138,813,080 | 5.47 |

| 53 | Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore | 13 | 24,856,418 | 5.23 |

| 54 | Gulf Islands National Seashore | 40 | 78,238,753 | 5.11 |

| 55 | Amistad National Recreation Area | 11 | 23,103,651 | 4.76 |

| 56 | Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park | 30 | 75,118,820 | 3.99 |

| 57 | Colonial National Historical Park | 20 | 54,819,943 | 3.65 |

| 58 | George Washington Memorial Parkway | 45 | 125,181,096 | 3.59 |

| 59 | Cape Cod National Seashore | 22 | 73,008,028 | 3.01 |

As you can see, adjusting for visits drastically affects each park’s position on this list. While Lake Mead had the most overall deaths, it ranked 17th on a deaths per visit rate. Blue Ridge Parkway, the most visited area, dropped all the way to 48 despite having the fourth most fatalities.

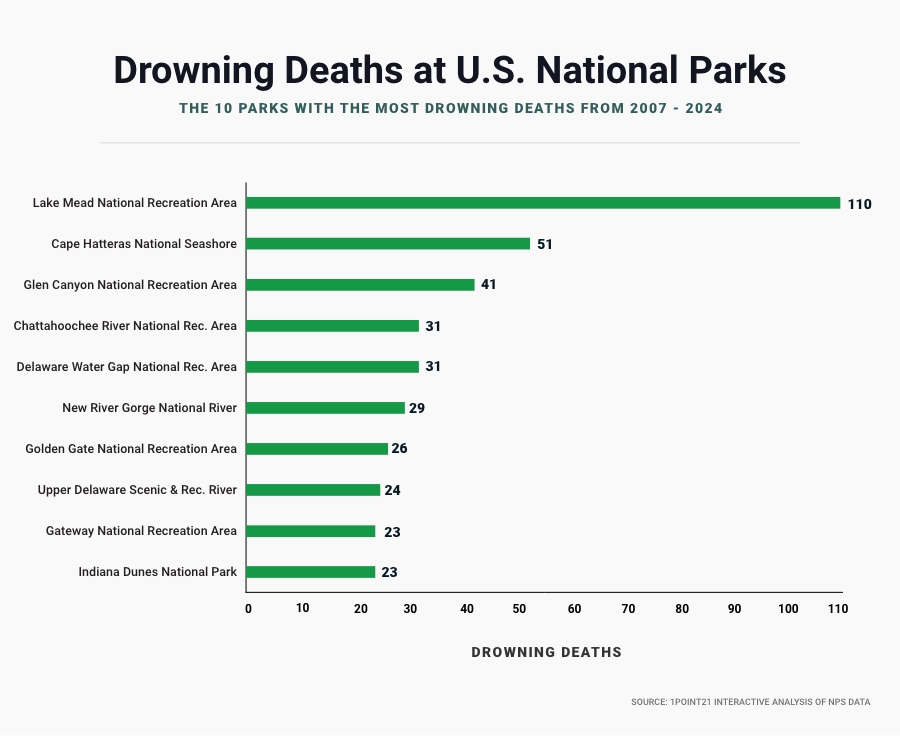

Lake Mead Leads the Way in Drowning Deaths

In addition to having the most overall deaths, Lake Mead National Recreation area led the way in drowning deaths as well. In fact, drowning was the leading cause of death at Lake Mead. With 110 drowning deaths, Lake Mead had over twice as many drowning deaths as the next highest park – Cape Hatteras National Seashore with 51. Glen Canyon National Recreation Area (41), Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area (31), and Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area (31) were third, fourth and fifth, respectively.

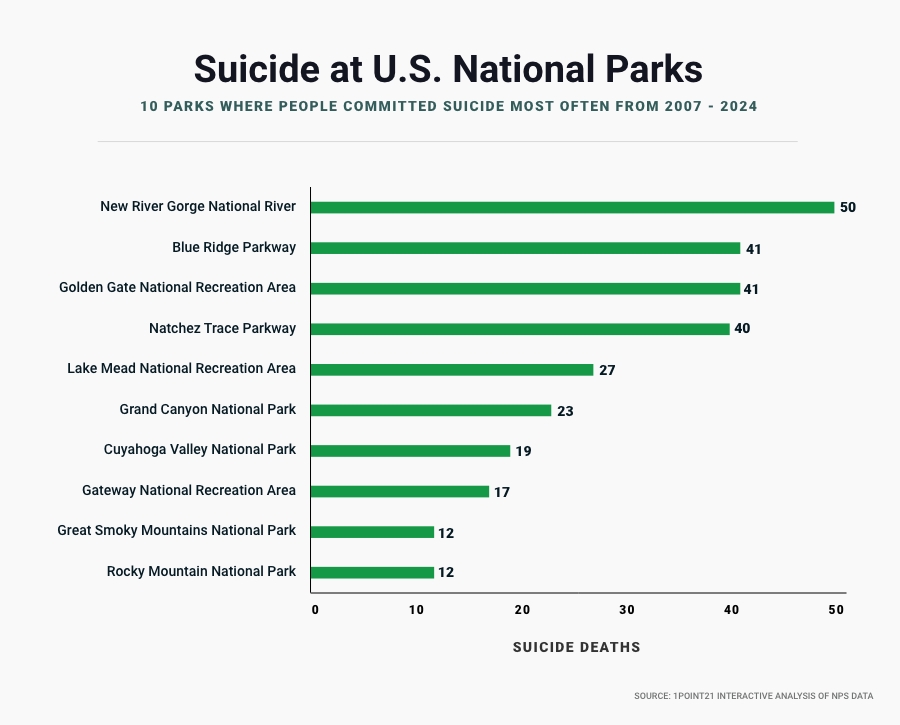

Multiple National Park Sites Have a High Number of Suicides

Unfortunately, three National Park sites in our analysis have a disproportionately high amount of suicides relative to the other listings. These include:

- New River Gorge National River, WV – 50 suicides

- Blue Ridge Parkway, VA & NC – 41 suicides

- Golden Gate National Recreation Area, CA – 41 suicides

These three sites alone accounted for over 46% of all National Park suicides from 2007-2024.

The high incidence of suicides at New River Gorge in southern West Virginia and Natchez Trace in Tennessee and Mississippi are likely due to bridges located within their respective areas that have become locally known as “suicide bridges.”

At 876 feet, the New River Gorge Bridge is the third-highest vehicular bridge in the United States. However, despite the staggering height, there are a distinct lack of barriers on the sides of the bridge. These conditions have made the bridge a famous location for BASE jumpers – and an unfortunately common site for suicides.

The cause for the high number of suicides in Blue Ridge Parkway are less clear. Considered America’s longest linear park, Blue Ridge spans 469 miles through Virginia and North Carolina, connecting Great Smoky Mountains National Park to Shenandoah National Park. There is no one site where suicides are more common, and there is seemingly no pattern for the high rate of suicides.

Other notable findings regarding suicide include:

- Natchez Trace Parkway, MS – 40 total suicides, the fourth most among all sites

- Lake Mead National Recreation Area, NV – 27 people committed suicide in the Grand Canyon, ranking fifth

In addition, suicide was the leading cause of death in two National Park sites: Cuyahoga Valley National Park in Ohio, and Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway in Minnesota and Wisconsin. In both sites, suicides accounted for 44% and 50% of all deaths, respectively, for the previous 17 years.

Methodology and Fair Use

We examined fatality data provided by the National Park Service for the years 2007 – 2024 ( the latest available full year).

Visitation data was pulled manually from the National Park Services website.

If you wish to report on our findings or use any of the visual or data elements of this analysis, please provide attribution by linking to this page.

A Note on National Park Designations

It is important to note that the National Park Service (NPS) does not just supervise and maintain National Parks. There are numerous designations used by the National Park System to help classify and preserve sites that have natural and/or historical significance. This includes:

- National Parks

- National Monuments

- National Preserves

- National Historic Sites

- National Historical Park

- National Memorial

- National Battlefield

- National Cemetery

- National Recreation Area

- National Seashore or Lakeshore

- National River

- National Parkway

- National Trail

Other sites managed by the National Parks System may have unique designations, such as the White House or the National Mall.

Despite all of these varying designations, the National Park Service has declared that all sites are equal in terms of legal standing, with equal privileges and rights as pertaining to the land. Therefore, our analysis includes all sites managed by the NPS and is not just limited to National Parks.

*Note: This study was originally published in 2019 and was be updated as necessary with the latest available data.